By Samantha Younan

This summer, Benjamin Humer (Year 4 EngSci) spent two weeks attending the Culham Plasma Physics Summer School in Oxfordshire, England. The trip was a culmination of months spent working with General Fusion, a Canadian startup focused on bringing clean, reliable energy through fusion technology to the grid by 2030.

“Everyone [from the company] was very excited that I was going,” says Humer.

“All the physicists were asking me about it and helping with the poster. It’s their life’s work. They get excited when someone young is excited about it and were all super supportive of the process.”

For Humer, tackling major engineering challenges in energy is part of a family legacy.

“My grandfather was an engineer who worked for BC Hydro, which allowed him to go all over the world and build hydroelectric dams,” says Humer.

“That seemed like an interesting way to help bring technology to people while still working on technical problems. That’s really what threw me into engineering.”

As a self-proclaimed “lego and physics kid,” Humer, who is originally from Vancouver, chose U of T for its EngSci program and because he was attracted to the idea of an uninterrupted co-op placement.

“The continuous co-op was a big draw instead of having it all sectioned off into little four-month chunks,” he says.

“I enjoyed being involved with all stages of a project, and in the 12 or 16 months of PEY Co-op, there is an opportunity to actually do that in a way you can’t in a shorter placement.”

Humer began working with General Fusion even before it was time to apply for his PEY Co-op placement. Starting in September 2023, he collaborated with researchers from the company as part of his undergraduate thesis, which focused on a key challenge in fusion energy: plasma formation.

The idea behind fusion is that atoms of light elements, such as hydrogen, get smashed together to form atoms of slightly heavier elements, such as helium. The process — the same one that powers the sun — releases tremendous amounts of energy but is extremely complicated to carry out in a controlled manner.

In most fusion reactors, the hydrogen fuel exists in the form of a plasma, a kind of super-heated fluid in which all the electrons have been stripped away. Because it would melt or destroy almost any material that could contain it, it must be held in place using magnetic fields.

“Imagine if you were holding plasma in a jar, but you couldn’t let a single particle of it escape and touch the edge,” he says.

“Like all fluids, the plasma will tend to expand to fill the entire volume of its container, so we have to use the magnetic fields to keep it from touching the walls.

“We had indications that instabilities were occurring, but we didn’t have confirmation what the specific instabilities were. I spent my time identifying the instabilities occurring and building a scientific basis for not only detecting these instabilities but also mitigating them in the future.”

Humer’s co-op with General Fusion began in May 2024. After just a few weeks, he found himself questioning some of his long held professional and personal ideas.

“I walked in thinking the problem was closer to solved than it was, which doesn’t discourage me from trying to solve it. There’s more meat on the bone from a scientific perspective,” he says.

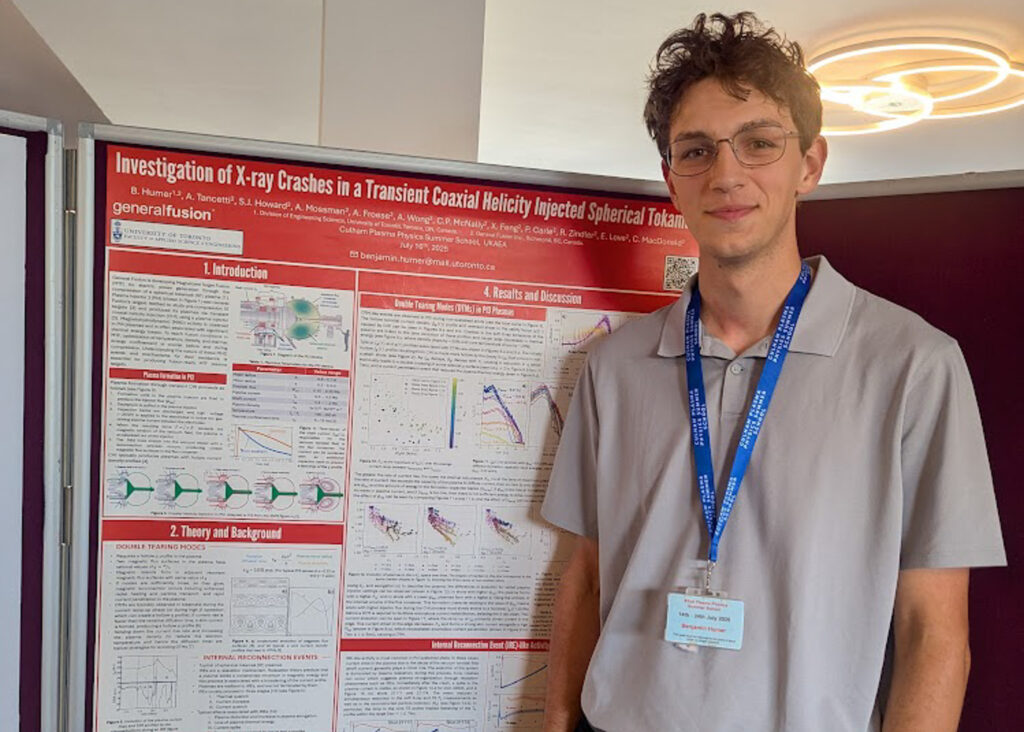

As part of the Culham Plasma Physics Summer School, Humer got to present a poster outlining the progress he’s made so far. He also got to meet many other young scientists interested in fusion.

“It’s lots of fun to connect with a generation of people that are going to be solving very similar problems,” says Humer.

“Plasma physics is not a big field so to have met 70 people that are the same age — it’s cool headed into the future thinking I’m going to stay in the same field. Problems of this scale require a lot of experts working together. I would like to be one of those experts.”

With the support of General Fusion, Humer plans to bring an updated version of his research to the Annual Meeting of the American Physical Society (APS) Division of Plasma Physics in California this November. After graduating from U of T, he plans to apply to graduate school, studying either plasma physics or applied math, and eventually earn a PhD.

“One piece of advice I’ll give is doing something outside of your co-op that is going to be recharging or interesting,” says Humer.

“My PEY Co-op experience has been really improved by living somewhere that I really wanted to live. I wanted to come back to Vancouver and that’s been great. I think the secondary pieces of the decision are as important to your experience as the specific company that you’re working for.”

This story was originally published in the U of T Engineering News.