A flexible plastic plate dotted with electrodes may not seem like something that belongs in a human mouth, but this student-developed device could help give some cancer patients back the ability to speak or swallow.

The innovative team behind the device are recent graduates Betty Bingruo Liu, Netra Unni Rajesh, Sulagshan Raveendrakumar, Jacob Smith, and Seung Doo (Charlie) Yang (all EngSci 1T9 PEY). Now their work has been recognized with the prestigious John W. Senders Award for Imaginative Design, which is presented to Year 4 University of Toronto engineering students for imaginative and successful application of engineering to the design of a medical device. The award is named after human factors and ergonomics pioneer Professor John W. Senders.

The team took on a challenge presented to them in EngSci’s biomedical systems capstone course by doctors from the Toronto General Hospital (TGH) Department of Head and Neck Cancer Surgery. For 17,000 Canadians diagnosed with tongue cancer every year, treatment often includes surgery to remove part of their tongue. This can leave patients with significant speech and swallowing impairment.

In rehabilitation, speech pathologists use electropalatography (EPG) devices to detect abnormalities in tongue motion and prescribe specific exercises to help restore functionality. Existing EPG devices are custom-made for each patient with 62 hand-wired electrodes, making them expensive and out of reach for many. The many electrodes also create a tangle of wires that impedes natural tongue movement and causes discomfort during exercises.

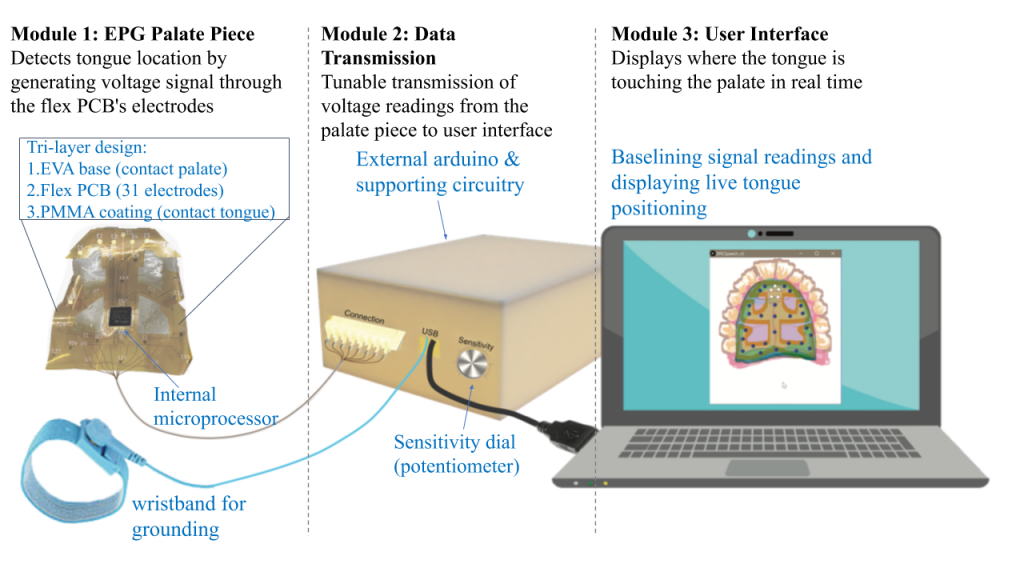

To address these limitations, the students created the EPICSpeech device (Electropalatography with Programmable Integrated Circuits for Speech Rehabilitation).

The team was inspired by the use of flexible printed circuit boards (PCBs) in medical applications such as diagnostic catheters and blood glucose monitors. Instead of a hard custom-fitted mouthpiece, EPICSpeech uses a flexible PCB that can be easily and cheaply mass produced. It allows the device to conform to the shape of a patient’s palate comfortably.

By embedding an internal processor and half as many electrodes as existing devices, the team also reduced the number of wires exiting from the patient’s mouth from 62 to just 8. “The key design feature was optimizing the number electrodes while giving users enough information to understand where their tongue is moving,” says capstone course instructor Professor Chris Bouwmeester. The smaller number of wires allows patients to move their tongue more naturally during exercises.

In collaboration with Dr. Douglas Chepeha, Dr. Majd Al-Mardini, and James Kelley from the TECHNA Institute, and Carly Barbone from Toronto Rehab at the University Health Network, the team also worked to meet the tough performance and safety requirements of medical devices. “The hardest part was integrating complex electrical components with a biocompatible base to fit safely in the mouth,” says Smith. “Many materials used in circuits are not biocompatible. We learned quickly how much work it is to combine electrical and biomedical components so they work within the mouth when covered with saliva.”

The project drew on knowledge the students had gained throughout their studies, Including engineering design, hardware circuits, programming, prototyping, biomaterials and biological assays. “This project is a great example of the power of multidisciplinary collaboration,” says Bouwmeester. “With a mix of students from EngSci’s electrical & computer engineering and biomedical systems engineering majors this team was able to achieve more advanced electrical hardware design and biological testing than a single discipline team would have.”

The resulting design is easier and cheaper to manufacture, can help speed up patient recovery, and can even help guide surgeons to better reconstructions. “This device has the potential to revolutionize rehabilitation of oral cavity patients,” says Dr. Chepeha. “It will help patients speak and eat after cancer treatment so they can go back to work and interact in society.”

Dr. Chepeha and his colleagues plan to continue working with EngSci students to test the device in patients and develop a wireless blue tooth interface to eliminate wires protruding from the mouth. They hope ultimately to license the device for distribution and support a speech and language pathologist to continue research on this innovative technology.