By Tyler Irving

Erin Richardson (Year 3 EngSci) was in Grade 9 when she decided she wanted to be an astronaut.

“We had a science unit on outer space, and I remember being completely fascinated by the vast scale of it all,” she says. “Thinking about how big the universe is, and how we’re just a tiny speck on a tiny planet, I knew I wanted to be part of exploring it.”

Richardson started following Canadian astronaut Chris Hadfield on social media and watching videos of his daily life on the International Space Station. She also started reading about aerospace and doing everything she could to break into the industry, including getting her Student Pilot Permit.

It was in a Forbes article about women in STEM that she first read the name of Kristen Facciol (EngSci 0T9).

A U of T Engineering alumna, Facciol had worked as a systems engineer at Canadian space engineering firm MDA before moving on to the Canadian Space Agency (CSA). When Richardson first learned about her, Facciol was an Engineering Support Lead, providing real-time flight support during on-orbit operations and teaching courses to introduce astronauts and flight controllers to the ISS robotic systems. Today, Facciol is a Flight Controller for CSA/NASA.

“I found her contact information and reached out to her,” says Richardson. “She’s been an amazing mentor to me over the last five years. We’re still close friends, and she’s really helped influence my career path.”

With Facciol’s encouragement, Richardson applied to U of T’s Engineering Science program, eventually choosing the aerospace major. After her first year, she landed a summer research position in the lab of Professor Jonathan Kelly (UTIAS), working on simulation tools for a robotic mobile manipulator platform.

“Working in Kelly’s lab piqued my interest in robotics as they could be applied in space,” she says. “Researching collaborative manipulation in dynamic environments will push the boundaries of human spaceflight – during spacewalks, astronauts work right alongside robots all the time.”

After her second year, Richardson travelled to Tasmania for a research placement facilitated by EngSci’s ESROP Global program. Working with researchers at the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, Australia’s national science agency, she created tools to analyze data collected during scientific mooring deployments, which help us learn more about our oceans over long periods of time. This work informs the design of next-generation mooring systems which, like space systems, must survive harsh and constrained environments.

Richardson was sitting in a second-year lecture when she heard the news that Canada had committed to NASA’s Lunar Gateway project, a brand-new international space station set to be constructed between 2023 and 2026. Unlike the ISS, which currently orbits Earth, the Lunar Gateway will orbit the moon and will serve both as a waypoint for future crewed missions to the lunar surface and as preparation for missions to even more distant worlds, such as Mars.

Energized, Richardson searched for a way to get involved. Her opportunity came in the fall of 2019, when she saw a posting on MDA’s job board. She immediately applied through U of T Engineering’s Professional Experience Year Co-op program, which enables undergraduate students to spend up to 16 months working for leading firms worldwide before returning to finish their degree programs.

Richardson started her placement in May 2020, right in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic. She and her employer quickly adapted.

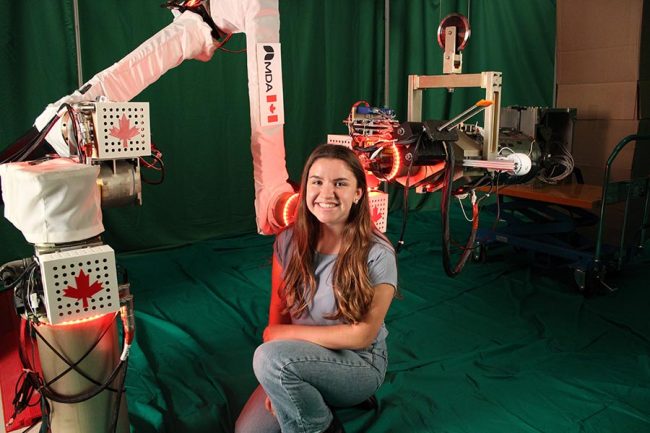

“I was working from home through the summer, but for my latest project I was able to go onsite to operate this robotic arm,” she says.

The robotic arm in question is a model of Dextre, a versatile robot that maintains the International Space Station. Richardson used it as a prototype part for the Canadarm3, which will be installed on Lunar Gateway.

Because the Lunar Gateway will be so far from Earth, Canadarm3 will be designed to be autonomous, able to execute certain tasks without supervision from a remote control station. Part of Richardson’s job is to create the dataset that will eventually be used to train the artificial intelligence algorithms that will make this possible.

In MDA’s DREAMR lab, Richardson guided the robotic arm through a series of movements and scenarios, with a suite of video cameras tracking its every move. She then tagged each series of images with metadata that will teach the robot whether the movements it saw were desirable ones to emulate, or dangerous ones to avoid.

“We had to capture different lighting conditions and obstacles of various sizes and colours,” she says. “My colleagues pointed out to me that because it’s me deciding which scenarios count as collisions and which ones don’t, the AI that we eventually create will be a reflection of my own brain.”

Apart from the opportunity to contribute to the next generation of space robots, Richardson says she’s enjoyed the chance to apply what she’s learned in her classes, as well as the professional connections she’s made.

“It’s my dream job,” she says. “I use what I learned in engineering design courses every day. I’m treated as a full engineer and a member of the team. The people I work with are extremely supportive and they talk to me about my dreams and goals. I love being surrounded by a team of talented and motivated people, all so passionate about what they do and about advancing space exploration. It’s an awesome opportunity for any student.”

This article was originally published in the U of T Engineering News.